Trees can talk to each other using a fungus, can trade resources, feed their seedlings and warn against dangers.

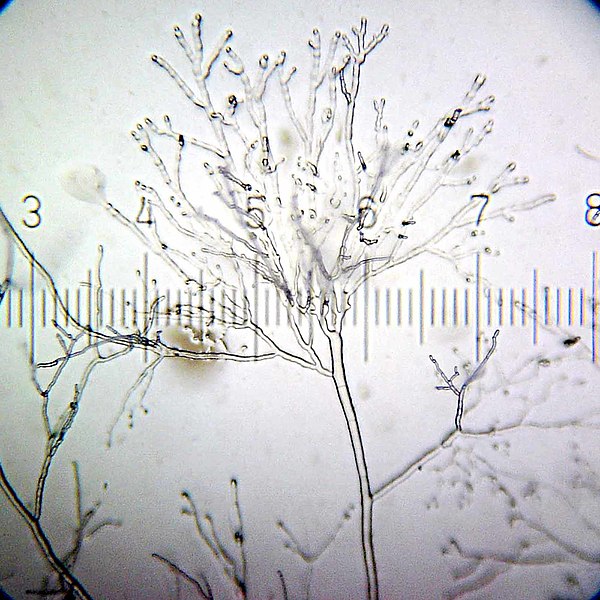

Mycorrhizal network

Imagine a way of hiding under your feet that allows plants to communicate and help each other. Yes, that’s it, and it’s made of mushrooms.

A way to accelerate the interaction between a large, diverse individual population. It allows a wide range of individuals to communicate and help each other. But it also allows them to present new forms of crime.

No, we’re not talking about the internet, we’re talking about mushrooms. Although fungi are the most familiar part of a fungus, most of their bodies are made of fine yarns known as a mycelium. We know that these yarns serve as a kind of underground internet that connects the roots of different plants. The tree in your garden is probably connected to a bush, a few meters away.

The more we learn about these underground networks, the more we have to think about plants. They grow quietly there. By connecting to the network, sharing food and information, they can help their neighbors - or they can sabotage unwanted plants by spreading toxic chemicals over the network.

Approximately 90% of land plants are in a mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. The 19th century German biologist Albert Bernard Frank identified the word mak mycorrhiza a to describe these partnerships.

The fungi were called the “Natural Internet” of the World. Plants provide nutrients in the form of carbohydrates. In contrast, fungi help plants absorb water and provide nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen through mycelia. Since the 1960s, mycorrhizae have been known to help grow individual plants.

Mushroom nets also strengthen the immune system of host plants. Because when a fungus digests the roots of a plant, it triggers the production of defense-related chemicals.

This event then makes immune system responses faster and more efficient, called “priming”. Attaching to mycelial networks makes plants more resistant to disease.

What the fungal internet could do was found decades ago. In 1997, Suzanne Simard of the University of British Columbia found one of the first pieces of evidence. Douglas showed that fir and paper birch trees could carry carbon with mines. Others have shown that plants can exchange nitrogen and phosphates in the same way.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A scientist (Zeng) and his team cultivated a tomato plant in a pot. Some plants were allowed to form mycorrhiza.

After the mushroom nets were formed, the leaves of one plant of each pair were sprayed with Alternaria solani, a fungus that caused early blight disease. Airtight plastic bags were used to prevent any surface chemical signaling between plants.

After 65 hours Zeng tried to infect the second plant in each pair. He realized that the likelihood of misbehavior was lower and that if they had micelles, they had a significantly lower level of damage when they did.

It’s not just the tomatoes that make it. In 2013, David Johnson of the University of Aberdeen and his colleagues showed that bean beans also used cork grids against impending threats.

Johnson found that pod seedlings that were not attacked by aphids, but were connected to the mushroom mycelium, activated their anti-aphid chemical defenses. Those who didn’t.

”There were some signals about the aphids among these plants, and these signals were transported through myxalial mycelial networks, Johnson says Johnson.

Just like in the human Internet, the fungal internet has a dark side. Our Internet is undermining privacy and facilitating serious crimes - and often allowing the spread of computer viruses. Likewise, the mushroom connections of plants means that they are never alone and that malicious neighbors can harm them.

For one thing, some plants are stealing something from this “Natural Internet”. Chlorophyll-free plants are available, so unlike most plants, they cannot produce their energies through photosynthesis. Some of these plants, such as phantom orchids, take the carbon they need from nearby trees with their mussels, both of which are attached.

Other orchids only steal when they are appropriate. These lar mixotrophs den can perform photosynthesis, but they also ”steal ez carbon from other plants using the fungus network that binds them.

This may not sound too bad, but it could be even worse.

Plants must compete with their neighbors for resources such as water and light. As part of this war, some release chemicals that damage competitors.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

This allelopathy can be found in trees, including acacia, sugary fruits, American sycamore and various types of Eucalyptus. They either release substances that reduce the chances of other plants installed nearby, or reduce the spread of germs around their roots.

But skeptic scientists doubt this. They say that harmful chemicals will be absorbed by the soil before it goes too far, or that germs will break down.

But perhaps the plants can solve this problem by utilizing underground mushroom nets that cover larger distances.

One of the most studied examples of allelopathy (chemical interaction between plants) is the American black walnut tree. It prevents the growth of many plants, including staples such as potatoes and cucumbers, from leaving their leaves and roots by leaving a chemical called jugalone.

Animals can also benefit from the fungal internet. Some plants produce compounds to attract friendly bacteria and fungi to their roots, but these signals can be collected by insects and worms looking for delicious roots to eat.

As a result of this increased evidence, many biologists have begun to use the term bit tree network ve to describe the communication services provided by fungi to plants and other organisms.

“These fungal networks make communication between plants, including those of different species, faster, and more effective,” says Morris. “We don’t think about it because we can usually only see what is above ground. But most of the plants you can see are connected below ground, not directly through their roots but via their mycelial connections.”

Fungal internet exemplifies one of the greatest lessons of ecology: apparently separate organisms are often interdependent and interdependent.

Comments