Listening to music while exercising activates the specific brain area and can help overcome fatigue

The new neuroimaging research sheds light on how people can help to protect themselves from the feeling of tiredness while exercising. The study, published in the International Journal of Psychophysiology, found that listening to music while exercising depends on increased activity in a particular brain region.

“As a researcher I have always been interested in unravelling psychophysiological mechanisms. The effects of music on exercise have been systematically investigated for more than 100 years, and we are still not completely sure how music enhances exercise performance, assuages fatigue, and elicits positive affective responses,” said study author Marcelo Bigliassi of Brunel University London.

“I have spent the past decade trying to answer this research question and, finally, after a series of fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy), EEG (electroencephalography), and fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) experiments, we can now understand how music is processed in the brain during exercise.”

In a study conducted on 19 healthy adults, participants revealed an MRI scanner and exercised using a hand-strengthening grip ring. Participants performed 30 exercise sets, each lasting 10 minutes. In some of these sets, the participants listened to Creedence Clearwater Revival from Grapevine.

Bigliassi and his colleagues have found that the presence of music is associated with more excitement during the exercise and that thoughts that are irrelevant to the task increase. They also observed changes in a specific area of the brain.

“Music is a very powerful auditory stimulus and can be used to assuage negative bodily sensations that usually arise during exercise-related situations. This psychophysical response is triggered by an attentional mechanism that will ultimately result in a more efficacious control of the musculature,” Bigliassi told PsyPost.

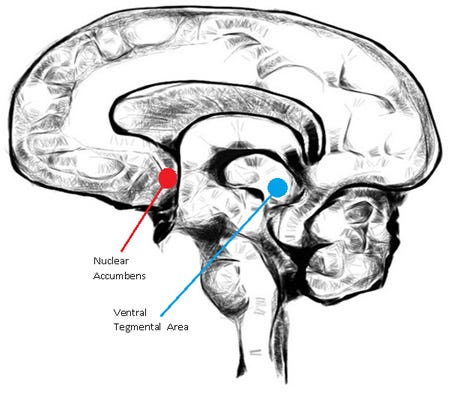

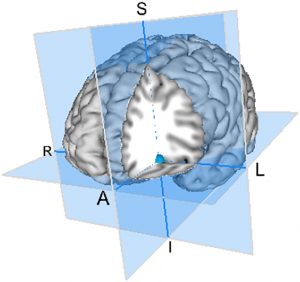

“What we have identified in this study was that the left inferior frontal gyrus activates (see the Figure below) when individuals exercise in the presence of music. This region of the brain appears to be a hub of sensory integration, processing information from external and internal sources (e.g., music and limb discomfort, respectively).”

“Increased activation of this region was negatively correlated with exertional responses, meaning that the more active this region the less fatigue participants experienced,” Bigliassi said. “It is important to emphasise that the practical implications of this study might be very similar to other applied studies in the field of sport and exercise. However, unravelling these mechanisms can actually open a new avenue for scientific investigation into the effects of sensory modulation on attentional responses and subsequent fatigue-related sensations.”

“For example, it is possible that other forms of stimulation (e.g., electrical) could lead to a series of domino reactions that might facilitate the execution of movements performed at moderate-to-high intensities and lessen fatigue. This could be used during the most critical periods of the exercise regimen, when high-risk individuals are more likely to disengage from physical activity programmes (e.g., individuals with obesity, diabetes, and etc.).”

Another of Bigliassi’s works used portable EEG technology to find the rest of the music while increasing the energy levels and entertainment they were walking with less focus. The effects were associated with an increase in beta waves in frontal and frontal-central regions of the cortex.

But Bigliassi doesn’t want to overdo the positive effects of music.

“I have some practical concerns about the exaggerated use of music and other forms of stimulation during exercise that are relevant to share. This is because, as humans, we are constantly trying to escape from reality and, also, escape from all forms of physical discomfort/pain,” he explained.

“We have learnt so much about the psychophysical, psychological, and psychophysiological effects of music in the past two decades that people are almost developing a peculiar form of stimulus dependence. If we continue to promote the unnecessary use of auditory and visual stimulation, the next generation might be no longer able to tolerate fatigue-related symptoms and exercise in the absence of music.”

“My view is that music and audiovisual stimuli can and should be used and promoted, but with due care,” Bigliassi said. “We should, perhaps, learn more about the joys of physical activity and develop methods/techniques to cope with the detrimental effects of fatigue (i.e., learn how to listen to our bodies and respect our biomechanical and physiological limitations).”

Comments