Blood flow to the brain during the thought process is so strong that it is enough for the head to outweigh the rest of the body if it was balanced horizontally before

This experiment was conducted by Angelo Mosso in the 19th century, but only noticed with the rise of neurobiology.

Scientists have uncovered new details about the man you might call “the da Vinci” of modern brain science. He was a physiologist named Angelo Mosso who lived in Italy during the 19th century, and until several years ago his manuscripts were mostly collecting dust in the archives of an Italian university.

Angelo Mosso

Angelo Mosso

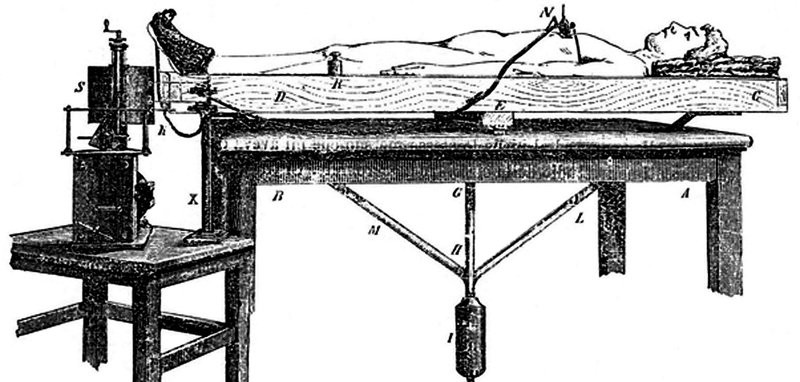

In his manuscripts, researchers found sketches of a contraption built in 1882: the first machine designed to watch the brain at work. It didn’t resemble modern brain scanners in any sense.

“It looks like some kind of medieval torture device. I mean it’s got a big strap to kind of stop the person moving around too much,” says David Field, a psychologist at the University of Reading and an expert on Mosso’s machine, called the “human circulation balance.” He even built a modern re-creation of it.

Mosso’s human circulation balance worked with a simple idea that was not relatively tested at the time: the brain needs more blood when they work hard.

Mosso would have volunteers lie down on a long wooden plank, carefully balanced on a fulcrum, like a seesaw. He calibrated for anything that might throw off the balance, like the rise and fall of the volunteer’s breathing. Then with everything secured, he’d ring a bell.

Mosso reasoned his volunteer’s brain would have to process the sound, requiring more blood, making it weigh more, which would tip the scale toward the head’s side. According to his manuscripts, that’s exactly what happened.

Angelo Mosso’s machine. Sandrone et al., 2014, Brain

Angelo Mosso’s machine. Sandrone et al., 2014, Brain

“It sounds like a romantic story, like a dream came true: trying to weight the thoughts,” says Stefano Sandrone, a neuroscientist at King’s College London. Sandrone is the lead scientist who uncovered Mosso’s manuscripts.

According to Mosso’s documents, Sandrone claims that the machine can sense the weight of various mental activities.

It remains unclear, though, exactly how well the human circulation balance worked. But, Sandrone says, like Leonardo da Vinci, Mosso had hit upon the right idea: Thinking and blood flow are intimately connected, a fundamental concept behind many of today’s brain scanning tools.

However, the human circulation balance had a flip side: The public began to put too much faith in it. In December 1908, a French newspaper reported that people believed the balance “would soon fully explain the physiology of the human brain” and treat mental illnesses.

In this way, Mosso’s invention shares some similarities with modern brain scanners, a brain scanning technology known as fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging); fMRI shows which parts of the brain work harder by watching how local blood flow changes.

Russ Poldrack, a psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin and an expert on brain scanning technology, says fMRI is an incredibly perfect tool.

The trouble is, that part of the brain is also associated with a lot of other emotions.

The brain is not that simple. But Poldrack has a guess as to why brain technology has often made it seem like it is.

“We’re sort of fascinated by seeing thought, which seems so nonmaterial — seeing it as a material thing,” he says. “I think people often feel like if they see it on an imaging scan, it’s real in a way that it isn’t real if it’s just being talked about.”

In the end, he says, the balance and fMRI are both machines, built by humans, imbued with limitations.

Comments